The Greatest Literary Enigma of All Time: The Synoptic Problem & A Possible Solution

- May 21, 2021

- 58 min read

Updated: Jul 26, 2023

Part I: A Literary Enigma

Leading biblical scholar Mark Goodacre describes the Synoptic Problem as “possibly the greatest literary enigma in history.”[1] Please do not mistake his words for hyperbole. This biblical puzzle has challenged, confounded, and captivated minds of theologians, philosophers, and frankly, all deep thinking individuals who have been clued in on the issue, for nearly two thousand years. And the debate over possible solutions to this literary enigma has really picked up steam in the past two and a half centuries, with some of the most important developments coming in the past hundred years alone.

I often hear atheists derisively say that they do not believe in scripture because they believe in “logic.” Despite their obvious indifference and/ or contempt toward scripture, I posit that even the most skeptical (i.e. the most “logical”) scholar will become captivated by the Synoptic Problem if they take the time to become familiar with the issue.

In other words, whether or not you see the spiritual value in scripture, I believe that you will still find the Synoptic Problem to be quite compelling. After all, at the root of the Synoptic Problem we are simply trying to determine what makes logical sense. This literary puzzle will challenge your problem-solving skills like a Rubik’s cube of words. Simply put, the Synoptic Problem is the brainteaser par excellence.

So, What is the Synoptic Problem?

Three of the four Gospels — Matthew, Mark, and Luke — share an undeniable literary connection, and because of this connection they are classified together as the “Synoptic” Gospels (thus leaving out the Gospel of John which is markedly different). The word synoptic can be broken down etymologically into syn which means “together” and optic which refers to “sight." As such, synoptic means “seen together.” These three Gospels are “seen together” as it were, because of the clear interdependence of their language. Matthew, Mark, and Luke share near verbatim passages, in a remarkably similar order. As a result, it is difficult to know what to make of this clear overlap. Herein lies the problem. Where one Gospel appears to be copying from another, that one seems to be in turn copying from the third, which in turn seems to be copying from the first. So basically, when one is grappling with the Synoptic Problem he or she is trying to figure out how to unravel this mystery of textual interdependence in order to deduce who is the source for whom, and where these teachings of Jesus originate -- the outcome of which means everything.

The ramifications of each interpretation cannot be overstated. One theory can prove the faith whereas another theory can disprove it. Understanding the order in which these Gospels were written is of the utmost importance. It helps us not only better understand who wrote each gospel, when they wrote it, and why they wrote it, but it can also give us insight into the reliability of the words. I will explain this in much more detail at the end of this.

To be given access to such profound answers, one has to contend with a very profound question:

What is the Most Logical Solution to the Synoptic Problem?

Before I dive into the leading hypotheses in the field, I want us to really understand how deeply interwoven these three Gospels actually are.

Let me break down this problem as simply as possible.

Suppose each of the Gospels is made up of the following elements:

Matthew = A + B + C

Mark = A + B + D

Luke = A + C + D

As you can see, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all share “A,” Matthew and Mark share “B.” Matthew and Luke share “C.” And lastly, Mark and Luke share “D.”

To put this in Biblical terms, the element “A” (which represents what all three gospels share) would be made up of things like Jesus’s Baptism, Jesus driving the money changers out of the temple, his death on the cross, etc. The element “B” (which represents what Matthew and Mark share) would be things like the emphasis on the use of parables, the calling of the disciples, the feeding of the four thousand, etc.. The element “C” (which represents what Matthew and Luke share) would be things such as the nativity, Jesus’ genealogy, the Lord’s prayer, etc. And lastly, the element “D” (which represents what only Mark and Luke share) would be things like the healing of demoniac in the synagogue or the teaching in the synagogue in Capernaum. Of the four elements A,B,C,D — D is by far the smallest.

I also could have added the elements E, F, G as follows:

Matthew = A + B + C + E

Mark = A + B + C + F

Luke = A + B + C + G

In this case, E, F, G would represent what is unique to each gospel respectively. For instance if you were to read all three gospels, you would find twenty percent of Matthew is unique to the other two (“E”), thirty five percent of Luke is unique to the other two (“F”) and only three percent of Mark is unique to the other two (“G”).

So, What are the Leading Theories?

I did not know whether I should present the leading theories to the Synoptic Problem in chronological order or if I should begin with the leading theory in academia today and work my way backwards. I have decided to go with the former, because I believe that seeing how the theories developed over time helps one to better understand the evolution of the Synoptic Problem, which in turn gives us a clearer sense of how we got to where we are today.

1. Augustinian Hypothesis

For the first few centuries following Jesus’s death, most (if not all) Church fathers believed that the order of the Gospels was actually the order of the Gospels. That is to say, the canonical ordering of the Gospels in our Bibles was believed to be their chronological order as well. This is known in academic circles as the Augustinian Hypothesis. The name is derived (as you might guess) from the teachings of Saint Augustine of Hippo — arguably the greatest theologian of all time. In the first part of his Harmony of the Gospels. Augustine wrote, “Now those four evangelists whose names have gained remarkable circulation over the world… are believed to have written in the order which follows: first Matthew, then Mark, thirdly Luke, lastly John.”[2] (11) Augustine, writing this in the fifth century, is not saying anything new; he is simply restating what church fathers had previously said on the matter. For instance, the second century church father, Irenaeus wrote:

“Matthew composed a written Gospel for the Hebrews in their own language, while Peter and Paul were preaching the gospel in Rome and founding the church there. After their deaths, Mark too, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, handed on to us in writing the things proclaimed by Peter. Luke, the follower of Paul, wrote down in a book the Gospel preached by him. Then John, the disciple of the Lord who had rested on his breast, produced a Gospel while living at Ephesus in Asia.”[3]

Irenaeus was a very important figure in the early church. He was a Greek Bishop who had once heard Polycarp preach.[4] Polycarp was a noted companion of the apostles and was said to be close with the apostle John.[5] Thus, Irenaeus was on the periphery of the apostles, and as such, his word was valued greatly.

What is more, the third century theologian Origen reiterated this same understanding of the Gospel order when he wrote, “I learned by tradition that the four Gospels alone are unquestionable in the church of God. First to be written was by Matthew, who was once a tax collector but later an apostle of Jesus Christ, who published it in Hebrew for Jewish believers. The second was by Mark, who wrote following Peter’s directives, whom Peter also acknowledged as his son in his epistle: ’The church in Babylon greets you … and so does my son Mark’ (1 Peter 5:13). The third is by Luke, who wrote the Gospel praised by Paul for Gentile believers. After them all came John.”[6]

The Augustinian Hypothesis is the traditional viewpoint, and it was the dominant view for over a millennium after the time of Augustine.

2. Griesbach Hypothesis (The Two Gospel Hypothesis)

While America was in the midst of a revolution — fighting for independence from Britain -- there was another revolution under way in the world of biblical scholarship. That is, in 1776 a German biblical scholar named Johann Jakob Griesbach not only pointed out the Synoptic Problem, but posited a possible solution.[7] Further elaborated by William Farmer in 1964, the Griesbach Hypothesis contends that Matthew’s Gospel was written first, just like the Church fathers believed. However, it was Luke who wrote second and Mark who wrote third.

Explaining the literary relationship between the Gospels, the Griesbach Hypothesis contends that Luke made use of Matthew when writing his Gospel, and then Mark made use of both Matthew and Luke as a compiler and harmonizer of the previous two.

3. The Two Source Hypothesis

A decade after Griesbach put forth his solution to the Synoptic Problem, another German theologian Gottlob Christian Storr changed the debate forever. For the first time in recorded history the traditional belief in Matthean Priority had been challenged. Storr is the earliest record we have of someone openly saying that Matthew was not the first Gospel to be written.[8] Rather, according to Storr, it was Mark who wrote the first Gospel.

In the early twentieth century, Storr’s idea was expanded upon at Oxford University by William Sanday, who put forth the Two Source Hypothesis -- the majority view among biblical scholars today.[9] The Two Source Hypothesis uses Storr’s contention that Mark’s Gospel was written first (i.e. Markan Priority) and that it was used as a source for both Matthew and Luke. What is more, the Two Source Hypothesis also posits that there was a second source for Matthew and Luke, which is now missing. This hypothetical missing source is often referred to as “Q” which stands for quelle — the German word for “source”. This hypothetical missing source is believed by proponents of the Two Source Hypothesis to be a gospel of the sayings of Jesus, similar in form and style (although not Gnostic substance) to the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas. This belief is often accompanied by the contention is that this missing source was used by both Matthew and Luke independently of each other.

In 1924, the The Two Source Hypothesis was expanded upon by B.H. Streeter. Streeter’s Four Document Hypothesis, elaborated on the Two Source Hypothesis (with which it was in complete agreement) by incorporating a hypothetical “M” source, which was the source for the original material in Matthew, and a hypothetical “L” source which was the source for the original material in Luke [10].

4. The Farrer Hypothesis

The second most widely held theory in academia today is the Farrer Hypothesis, which is named after biblical scholar Austin Farrer. In his groundbreaking 1955 essay, “On Dispensing with Q,” Farrer argued for Markan priority without the reliance on a hypothetical missing source like in the Two Source Hypothesis. The Farrer Hypothesis contends that Mark wrote first, after which Matthew wrote using Mark as a source. And then Luke wrote his Gospel using Mark and Matthew as his sources. Mark Goodacre (who I quoted at the beginning of this essay) is today’s leading proponent of the Farrer Hypothesis. In his insightful book, The Case Against Q, Goodacre furthers Farrer’s argument and shines a light on the biggest problem with the Two Source Hypothesis, which is, if Luke was aware of Matthew’s Gospel, then the need for a missing source of Jesus’ sayings is eliminated.[11]

Or another way to look at it, Luke’s independence of Matthew is what separates the two leading theories in the Synoptic Problem debate.

So, Are There Other Theories that Are Less Likely?

There are three minority views in this field that I believe are worth noting. I like studying these arguments especially, because I think it would be amazing if the answer to this literary enigma had been overlooked this whole time by the wisest among us. For as it says in scripture “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever I will thwart” (1 Corinthians 1:19).

1. Independence/ Orality and Memory Hypothesis

I often conflate the Independence Hypothesis and the Orality-Memory Hypothesis, because there is a clear overlap in these two theories that is difficult to ignore. The former believes that the Gospels developed in the purest way possible, while the latter believes that they formed in the most natural way possible. The Independence Hypothesis posits that all three gospels formed independently of each other, and any similarities that exist are merely "coincidental"(or as many Independent Theorists might say "an act of God"). And the Orality and Memory Hypothesis — which contends that the gospels were first passed on orally and not written down until later — gives the Independence Hypothesis an explanation for the overlap in language. That is, every one kept hearing the same stories over and over again, so by the time they were written down there were bound to be similarities.

Perhaps I am doing a disservice to both theories by linking them together in such a way. Nevertheless, conflating these theories is quite common among scholars — even scholars who are proponents of one theory or another.

In The Synoptic Problem: Four Views, biblical scholar Rainer Riesner argues in favor of the Orality and Memory Hypothesis, and he, does so by conflating it with, and differentiating from the Independence Hypothesis. Riesner refers to both theories in tandem as the “Tradition Hypothesis.” It is referred to as the “Tradition Hypothesis” because the proponents of the Independence Hypothesis often argue in favor of the Augustinian ordering of the Synoptics; which is to say, they are in agreement with the traditional church point of view.

Reisner cites some highly acclaimed proponents of the Independence Hypothesis as a defense of his own advocacy for the Orality and Memory Hypothesis, but then he undercuts their research in an attempt to bolster his own, saying, “Even the Tradition Hypothesis in its purest form is defended today. Eta Linnemann and F. David Farnell explain the Synoptic evidence only by the different memories of eyewitnesses. To a certain degree their views are influenced by dogmatic assumptions on the inerrancy of Scripture. Other scholars argue on purely scientific grounds for the Tradition Hypothesis.”[12]

What Riesner is doing here is differentiating his Orality and Memory Hypothesis — which according to him is based on scientifically studying the oral traditions of cultures at the time — from proponents of the Independence Hypothesis like Eta Linnemann, whose book “Is There a Synoptic Problem?” contends that all three Synoptic Gospels came about completely independent of each other. Linnemann’s argument, as Riesner illumines, is “dogmatic” based on “the inerrenancy of scripture” rather than on a strictly ”scientific grounds.”[13] This may, however, be an unfair assessment of Linnemann’s research and the Independence Hypothesis. As Edwin Reynolds argues, “Although [Linnemann] writes with an apologetic goal, that in an of itself does not invalidate the objective nature of the data she submits for evaluations.”[14]

2. Wilke Hypothesis

In 1838, theologian Christian Gottlob Wilke preceded Austin Farrer with his own two gospel hypothesis with Markan priority. However, unlike Farrer, Wilke thought that Luke preceded Matthew. The Wilke Hypothesis contends that Mark wrote first. Luke then wrote his Gospel and used Mark as his source. Lastly, Matthew wrote his Gospel using both Mark and Luke as his sources. Any hypothesis that places Luke earlier than Matthew is a minority view. Nonetheless, there have not only been theories of Luke written before Matthew, but there are also theories with complete Lukan priority — where scholars have argued that Luke wrote his Gospel before both Matthew and Mark.

Perhaps one of the reasons that Lukan priority is so difficult to accept is because in the prologue of the Gospel of Luke. The evangelist is quite explicit about using sources for his writing. He writes, “Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things which have been accomplished among us, just as they were delivered to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word” (Luke 1:1-2).

We naturally assume that the Gospels of Matthew and/or Mark are “the eyewitnesses and ministers of the word” that Luke is referring to here. There are some scholars, however, who believe we may be jumping to conclusions.

3. The Priority of Luke (Jerusalem School)

The first one to posit complete Lukan priority among the Synoptics was William Lockton in 1922. Theologian and member of the Jerusalem school, Robert Lisle Lindsay, put forth a similar argument in the 1960s, unaware of Lockton’s previous scholarship on the matter. The Jerusalem School Hypothesis (of which Lindsay is a proponent) contends that the original gospels were written in Hebrew and then translated into Greek. This translation (or set of translations) is known as the Proto-Narrative. Both the Proto-Narrative, and the hypothetical Q source of sayings (which we described earlier in the Two Source Hypothesis) were used by Luke, who wrote his Gospel first. Mark then used Luke and the Proto-Narrative as his sources. And then Matthew used Mark and the Proto-Narrative as his sources.

The Ramifications of Each Theory

Earlier in this essay I mentioned how each of these theories carries with it its own far reaching ramifications. I will give you some examples at this time of what I mean by that. For instance, if the Gospel of Matthew was not written first, then there is no way that it could have been written by the Apostle Matthew. Why do I say that? Because if Matthew did not write first, then based on the literary connection among the Synoptic Gospels, it means that he would have likely copied Mark (and/or possibly Luke) as a source. Thus, it would not make sense for Matthew, who was an apostle of Jesus (i.e. eye witness to the living and risen Christ) to copy Mark or Luke who were not apostles. Nevertheless, to contend that Matthew wrote first, one has to explain why Mark would copy Matthew and Luke in the way that he does, leaving out so many important events in the life of Jesus such as his birth, his sermon on the mount, and his resurrection appearances.

What is more, despite the fact that the Augustinian Hypothesis places Mark second in the Gospel order, even Augustine himself could sense that this was highly unlikely. In fact, the Augustinian Hypothesis is often referred to nowadays as the “Classical Augustinian Hypothesis” because Augustine seemingly changed his mind in the midst of his research, and thus developed a second opinion on the matter. By the end of his Harmony, Augustine was less aligned with Origen, Ireneaus and other church fathers, and more aligned with the Johann Jakob Griesbach, who believed it was Matthew, then Luke, then Mark, each using the gospel(s) that preceded them as a source.

Augustine explains his new hypothesis as follows, “the more probable account of the matter, [Mark] holds a course in conjunction with both [the other Synoptists]. For although he is at one with Matthew in the larger number of passages, he is nevertheless at one rather with Luke in some others.”[15]

Augustine’s change of heart on the matter is explained in The Synoptic Problem: Four Views by David Barrett Peabody, who contends, “After completing his [Harmony] with all the material that has a parallel in any other of the other three Gospels… Augustine affirms what he says is his ‘most probable’ view of Mark — namely, that Mark combined the contents and themes of Matthew’s and Luke’s Gospels, which, if intentional, would require that Mark’s Gospel be composed after and dependent upon the other two Synoptic Gospels.”[16]

This leads me to what I believe to be the solution to the Synoptic Problem. Despite the Two Source Hypothesis and the Farrer Hypothesis being the two most widely held theories among scholars in the field today, I am actually in agreement with Saint Augustine on this matter. No, not Augustine when he agreed with the traditional church viewpoint, but rather, Augustine when he was in agreement with Griesbach. In other words, I believe that Matthew wrote first, then Luke wrote using Matthew, and then Mark wrote using both Matthew and Luke. In the next part of this essay I will go into great detail, arguing for each position in the ordering, doing a side by side analysis of scripture, and setting it against the historical backdrop in which is was written.

Part II: A Possible Synoptic Solution

So, What Is the Solution to the Synoptic Problem?

Instead of going through each of the theories one-by-one, going over the merits and deficiencies of each. I have decided to simply put forth an argument in favor of the theory that I hold — the Griesbach Hypothesis — and in so doing, I hope to point out the pros and cons of the other aforementioned theories along the way.

Historical Context

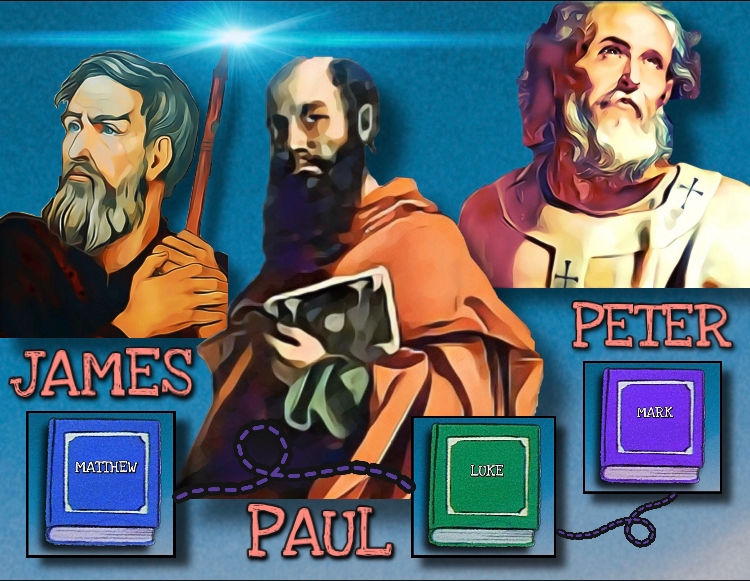

To understand how each Gospel developed, one must first understand how the early church developed. For it is not only form and textual criticism that illumines possible answers to the Synoptic Problem (and we will see how in the next section), historical context is also a path way to our theological understanding on the matter. It is my contention that the Synoptic Problem of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, is as much about the early pillars of church, James, Peter, and Paul, as it is about the Evangelists and their possible sources. The current mainstream view of the early church is often oversimplified and misunderstood as something akin to: Jesus died on the cross and then Peter, as Christ’s closest disciple, became the leader of the new church. Perhaps, this view is derived from the passage in Matthew’s Gospel, where Jesus says to Peter, “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it” (Matthew 16:18). Couple that with the fact that Peter is honored in the Roman Catholic Church as the first Pope, and it makes sense where this misunderstanding and oversimplification of early church leadership comes from. Despite all of that, the way in which the early church really developed is a lot more complicated. As we know, in real life things are a bit more political and controversial. After the death of Jesus, the de facto leader of the church was not Peter as most assume, but rather Jesus’s brother James. And more than just his familial relationship to the Lord, it was James’s relationship with the scriptures (i.e. the Law) that made him the ideal choice of many in the new church.

James: The First Leader of the Church

As early church chronicler, Hegessippus wrote of James,

“[Administration of] the church passed on to James, the brother of the Lord, along with the apostles. He was called ‘the Just’ by everyone from the Lord’s time to ours, since there were many Jameses, but this one was consecrated from his mother’s womb. He drank no wine or liquor and ate no meat. No razor came near his head, he did not anoint himself with oil, and took no baths. He alone was permitted to enter the sanctum, for he wore not wool but linen. He used to enter the temple alone and was often found kneeling and imploring forgiveness for the people … Because of his superior righteousness he was called the Just and Oblias — meaning, in Greek, ‘Bulwark of the people’ and ‘righteousness’ — as the prophets declare regarding him.”[17]

According to Hegessippus, it is clear that the reason that James was the ideal choice of leader for so many early followers of Jesus, was not only because he was “consecrated” so to speak in the same womb as the Lord, but also because he was the epitome of righteousness. James was an extremely devout Jew, who was not one to break with tradition on a whim. In fact, we can infer from the Gospels (Mark 3:19-21, Matthew 13:53-57) that he and the rest of his siblings were very much embarrassed by Jesus while he was alive, seeing him as perhaps misguided in regards to Jewish tradition. So for a man as devout as James to admit that Jesus was indeed the promised Messiah was extremely convincing for not only the religious radicals but also for strict adherents of the Law as well. James, at once, represented Jewish tradition, and also the new church. To put a finer point on it: he represented a change, but not that much. For many, this is what made James the ideal first leader of the church; he was very much seen as a continuation of the Old way.

What I find particularly noteworthy in this discussion of early church leadership, is that the Book of Acts (the first history of the early church) focuses primarily on the actions of two individuals: Peter and Paul. This implies that these two men were the original church leaders. I believe that this further adds to the common underestimation of James’s importance in the early church and the assumption of Peter’s primacy. Nevertheless, the truth has been right in front of our eyes the whole time. James is figuratively and literally right at the center of it all — like a true leader. That is to say, in Acts chapter fifteen (15 of 28 chapters is just about right in the center as it were), we read of how there was a meeting of all of the leaders of the early church in Jerusalem to debate about why and how to allow Gentiles into their new church. Peter and Paul each spoke on the matter, each addressing the virtues of Gentile acceptance, but it was not until James spoke on the matter that the issue was resolved. As it is written,

“James replied, ‘Brethren, listen to me…my judgement is that we should not trouble those of the Gentiles that turn to God, but should write to them to abstain from pollutions of idols and from unchastity and for what is strangled and from blood. For from early generations Moses has had in every city those who preach him, for he is read every sabbath in the synagogues.’” (Acts 15:1319-21).

After James speaks on the matter, contending that the Gentiles should follow at least some of the Law, we read, “Then it seemed good to the apostles and the elders, with the whole church, to choose men from among them and send them to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas.” In other words, James was the last word on the matter.

As we can see, the new church went along with whatever James decreed.

What I also want us to notice in the passage is how James is saying how they (i.e. the church apostles and elders) should write in order to explain what is expected of new members. This brings us to the Letter of James. In which, he does just that — laying out his theology of the new church. Before I get into the theology of James and its impact on the church — and by extension its impact on the Synoptic Problem — I want us to get a couple of things out of the way first. We need to address two important questions: Did James the Lord’s brother, actually write the letter that bears his name, and when was the Letter of James written? To answer the first question, I turn to the work of biblical scholar John A.T. Robinson who notes that, “the argument for pseudonymity is weaker [in the Letter of James] than with any other of the New Testament epistles.”[18] This conclusion that James was in fact the author of the letter helps us to better date the letter. Robinson puts forth the date of 47-48 AD, which makes James the earliest piece of writing in the New Testament.[19] This makes a lot of sense in light of the content of the letter. Scholar E.M. Sidebottom notes how the theology of the letter gives “an impression of an almost precrucifixion discipleship.”[20] This precrucifixion impression is due to the fact that in the letter, James only mentions Jesus’s name twice; and nowhere does he describe any part of Jesus’s life, death, or resurrection. As Robinson puts it, “there is nothing that conflicts with or goes beyond mainstream Judaism.” The Letter of James, and the theology within, are very much in line with the character of James as described by early church historians. James represented a deep connection with Jewish tradition with just a small sprinkling of Christ in the mix. The letter that bears his name could be described in very much the same way.

It is only by understanding who James is in the early church and the theology that he represents that one can begin to approach the Synoptic Problem with the right historical framework to understand the earliest written developments in the church. Let us look at the theology in the Letter of James to see what I mean.

James' Theology: Faith and Works

One of the central themes of the letter of James, is the concept of faith. In chapter one, the power of faith is explained, “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God who gives to all men generously and without reproaching, and it will be given him. But let him ask in faith, with no doubting, for he who doubts is like a wave of the sea that is driven and tossed by the wind. For that person must not suppose that a double-minded man, unstable in all his ways, will receive anything from the Lord” (James 1:5-8).

For James, faith in God can lead to abundance in one’s life. However, there is a caveat: one must believe in God without doubting at all. For doubt can suppress the divine rewards. All that being said, there is an issue for some with the power of faith as described by James. In chapter two, it is written:

“What does it profit, my brethren, if a man says he has faith but has not works? Can his faith save him? If a brother or sister is ill-clad and in lack of daily food, and one of you says to them, ‘Go in peace, be warmed and filled,’ without giving them the things needed for the body, what does it profit?’ So faith by itself, if it has no works is dead” (James 2:14-17).

It seems quite clear that James is saying that the power of faith can only go so far. In fact, James goes on to say, that “faith [is only] completed by works.” According to James, “without works of the law faith is dead.” As one might guess, based on the character of James, this theological stance of doing works of the law is very much in line with the Jewish tradition. That does not mean, however, that many in the early church did not find this view to be highly controversial.

Paul: the Other First Leader of the Church

Let us step back from James for a moment, and turn our attention to the other first leader of the church — Paul. Unlike James and Peter, Paul did not know Jesus personally, and as such his claim to authority in the early church was tenuous at best.

In his letter to the Galatians, Paul writes of spending over two weeks with James and Peter in Jerusalem, saying, “I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas [i.e. Peter], and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother. (In what I am writing you, before God, I do not lie!)”

From Paul’s point of view, this meeting is important for people to know about, and believe him (according to the parenthetical in the passage above), because he knows how he is seen in the eyes of skeptics. He was not a real apostle in the true sense of the word, meaning, he was not an actual follower of Jesus in life and thus a not an easy-to-believe eyewitness to the risen Jesus. As such, it was very important for others to know that he associated with those who were. And Paul even goes on to add, “and when they perceived the grace that was given to me, James and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised” (Galatians 2:9)

What Paul is saying here is that James, Peter, and John — the three leaders of the church — gave him their stamp of approval. What is more, the way in which they were preaching to the Jewish people, so, too, should Paul do unto the Gentiles. Paul is clearly admitting that his mission to the Gentiles was secondary (at least historically) to that of Peter and James to the Jews.

Paul vs. James

It would seem, from the above passage, that everyone is aligned in their shared mission. Nevertheless, as Paul continues his letter to the Galatians he tells you of a rift that developed among them. Paul continues on, “But when Cephas came to Antioch I opposed him to his face, because he stood condemned. For before certain men came from James, he ate with the Gentiles; but when they came he drew back and separated himself, fearing the circumcision party. And with the rest of the Jews he acted insincerely… But when I saw that they were not straightforward about the truth of the gospel, I said to Cephas before them all, ‘If you though a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?’ We ourselves, who are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners, yet who know that a man is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Christ Jesus in order to be justified by faith in Christ, and not by works of the law, because by works of the law shall no one be justified.” (Galatians 2:11-16).

Paul's Theology: Faith Alone

It's as if everything we have said thus far has come to a head in this passage. The theology of James, which, as we noted earlier, is essentially a continuation of Jewish tradition — represented by the teaching in his letter that one is justified by faith and works of the law — is being challenged by Paul, who in direct opposition, says we are “not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ.” So to put it all in context, the story that Paul is telling here is that Peter had come to visit him and the Gentiles in Antioch and everything was going fine and everyone was getting along — that is, until more men were sent there by James. It was at this point that Peter withdrew from the Gentiles, in favor of the Jews. This causes Paul to call him out for his actions. This action of siding with the Jews sent by James is analogous in Paul’s eyes to preaching the wrong gospel, a gospel that preaches of faith and works, rather than simply faith in Christ alone. Simply stated, Paul is poignantly framing this story, of his opposition to the theology of James, by arguing against it via the actions of Peter where he literally chose the Jews over the Gentiles in Antioch.

So Who is the First Leader of the Church?

Let us review: We have James, the Lord’s brother, who was the first leader of the church and represented a continuation of much of the Jewish tradition. And we have Paul, who is not an apostle in the conventional sense of the word, placing himself in direct opposition to those who were the closest to Jesus, opposing any view that requires faith to be coupled with works of the law in order for one to be saved. What is more, we also have Peter, who has found himself figuratively and literally between James and Paul. I will delve deeper into Peter’s theology shortly.

For now, I think it is important to turn to an earlier passage of Paul in his Letter to the Galatians, where he delineates the shared, yet distinct mission of he and Peter, saying, “I had been entrusted with the gospel to uncircumcised just as Peter had been trusted with the gospel to the circumcised (for he who worked through Peter for the circumcised worked though me also for the Gentiles)” (Galatians 2:7-8).

James, Peter and Paul and the Order of the Gospels

This passage brings us to the matter at hand. We are discussing the Synoptic Problem and the order of the Gospels. Notice how Paul in the above passage describes two different gospels: one for the circumcised, which is to say the Jewish community, and one for the uncircumcised, which is to say for the Gentiles. This is not simply the metaphor that most scholars seem to think it is. I believe that Paul is being quite literal about there being two distinct Gospels.

It is my contention that “the gospel for the circumcised” is analogous to what we know today as the Gospel of Matthew, and that the Gospel for the uncircumcised is analogous to what we know today as the Gospel of Luke. What is more, I will show you how Matthew connects with James and how Luke connects with Paul. And of course, Peter is also a part of this, and that is where the Gospel of Mark comes in (but I will return to Peter and Mark later). For now let us look at how the first two letter writers, James and Paul, are connected with the first two gospel writers, Matthew and Luke.

Dating the First Two Gospels Via James and Paul

First I need to establish some dates for these writings, so that we can construct an historical framework and we can see how it all fits together. I had said earlier how scholars like Robinson dated the Letter of James circa 48 AD, making him the first letter writer of the New Testament. This flies right in the face of the predominant opinion among scholars today, which is that Paul wrote first. The majority of these scholars usually claim that the Letter to the Galatians (or to a lesser extent, the Letter to the Thessalonians) was the earliest letter of the New Testament. Nevertheless, as Robinson’s research demonstrates, Paul is clearly responding to James. As Robinson writes, “[Paul’s letters read] more intelligibly as an answer to James rather than vice versa. As a reply to Paul’s position James’ argument totally misses the point; for Paul never contended for faith without works.”[21] Furthermore, as Robinson argues, “James is addressing all who form the true, spiritual Israel, wherever they are. And he can address them in such completely Jewish terms not because he is singling them out from Gentile Christians but because, as far as his purview is concerned, there are no other Christians.”[22]

Please do not mistake this as evidence of James’s prejudice against Gentiles, but rather as evidence of the time in which his letter was written. As scholar, T. Zahn points out in Introduction to the New Testament, when James was writing his letter it was so early in the history of the church, that “Israel constituted the entire church” and this was only true for a small window of time in the very beginning of the church.[23]

So we have established that James was the first leader of the church, and the first letter writer of the New Testament, and that he was speaking directly to the Jewish people. And we have also established that Paul was an outsider, who sees his mission as spreading the Word of the Lord to the Gentiles. The problem, however, is that the message James preaches of faith and works is at odds with the faith alone message in the letters of Paul. Now let us bring in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke to help us better understand this tension in the early church.

The Gospel of Matthew: James' Theology

Now I want to establish the connection that exists between the theology of James and the Gospel of Matthew in contrast with the connection that exists between the theology of Paul and the Gospel of Luke. In other words, I want us to look at the root differences between the “gospel for the circumcised’ and the “gospel for the uncircumcised.”

First, let us begin with the clear connections between the Letter of James and the Gospel of Matthew. As Robinson contends, “There is no doubt that it is Jesus’ teaching, particularly found in the Sermon on the Mount and the Matthean tradition, that lies behind everything that James says.”[24]

Let us look at some clear textual examples of where the theology of the two overlap.

Both James and Matthew explain the dangers of valuing worldly goods (which time will ravage) over the value of God’s rewards (which are unending). In the Letter of James it is written,

“Come now you rich, weep and howl for the miseries that are coming upon you. Your riches have rotted and your garments are moth-eaten. Your gold and silver have rusted, and their rust will be evidence against you and will eat your flesh like fire.” (James 5:1-3).

And in the Gospel of Matthew, using near identical language, the same point is made:

“Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal” (Matthew 6:19-20).

Both of these passages, James and Matthew, share the same point and the same language. Each are stressing the lack of importance one should put in earthly riches, for they are subject to time, decay, and ruin represented by the moth’s devouring them and metals rusting them in both passages.

More than just the same outlook and the same language about the overvaluation of worldly goods, the Letter of James and the Gospel of Matthew also share the same outlook on pride and humility. In James it is written,

“God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble…Humble yourselves before the Lord and he will exalt you” (James 4:6,10).

And likewise, in Matthew it is written:

“He who is greatest among you shall be your servant; whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted” (Matthew 23:11).

James and Matthew are again using near identical language to make the same point. Much like the previous point about worldly goods, this point about humility is about not overvaluing yourself in your own eyes, but rather, in realizing that your worth is derived from the Lord alone. In other words, only the Lord can judge. This brings us to our next James-Matthew comparison. Both speak about the dangers of judging. In James it is written,

“And the tongue is a fire. The tongue is an unrighteous world among our members, staining the whole body, setting on fire the cycle of nature and set on fire by hell…from the same mouth come blessing and cursing” (James 3:6,10).

And in Matthew it is written,

“But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother shall be liable to judgment; whoever insults his brother shall be liable to the council, and whoever says, ‘You fool! Shall be liable to the hell of fire’” (Matthew 5:22).

The message in both James and Matthew is essentially the same: by judging others we condemn ourselves to the fires of Hell.

The overlap in theology and language between the Letter of James and the Gospel of Matthew should be apparent by now. The question that remains is: does the Gospel of Matthew, which shares much with James, also express a continuation of Jewish tradition and a strict adherence to the law like that found in James? As a matter of fact, it does.

As we said earlier, the Letter of James was written at a time so early in the church, that it was before Gentile Christians were even a thing. This may explain why in the Gospel of Matthew it is written, [Jesus] said, ‘Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel’ (Matthew 10:5-6). It is clear that this form of Christianity is very much of-and-for the Jewish people. What is more, Jesus seems very much aligned with the theology of James in the Gospel of Matthew, when he says,“Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfill them. Truly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the law until all is accomplished” (Matthew 5:17-18).

Matthew’s Jesus seems to be very much aligned with the theology of James, which was clearly a continuation of Jewish tradition. These two passages in Matthew stand in stark contrast to the message Paul was preaching. For one thing, Paul’s mission was to preach to the Gentiles, so this idea in Matthew of only saving the lost sheep of Israel and not going among the Gentiles, is ostensibly in clear opposition to everything that Paul was doing. What is more, as we already noted, Paul preached of one being justified by faith alone, so any notion of justification coming from works of the law (James and Matthew are suggesting) was completely wrong and misguided.

Think of the historical context here. We have James’ the Lord’s brother who is the Bishop in Jerusalem/ leader of the early Church, and represents a continuation of Jewish tradition. This theology is picked up by Matthew’s Gospel, and weaved into the narrative of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Matthew, like James before him is speaking directly to the Jewish people; so much so in fact that Matthew’s Gospel was the only one that was originally written in Hebrew.[25] (All three others were originally written in Greek.) This is why Paul feels the need to distinguish between a gospel for the circumcised and a gospel for the uncircumcised. Enter Paul’s missionary companion Luke.

The Gospel of Luke: Paul's Theology

The early church father Ireneaus described Luke’s Gospel as follows: “Luke the follower of Paul, wrote down in a book preached by him.”[26] Moreover, Eusebius, who is our source for Ireneaus’s words, furthers this point when he says, “They say Paul was actually in the habit of referring to Luke’s Gospel whenever he used the phrase, ‘According to my gospel.’”[27] What is more, Origen similarly writes that “Luke…wrote the Gospel praised by Paul for Gentile believers.”[28] So as we can see from the record of these three church fathers, Paul was deeply connected with the Gospel of Luke — whether that means it was based on his teaching, or if it just means that it was aligned with his theology, — which is to say directed towards Gentiles — is unclear from these writings. Nevertheless, painted in this light, it places Luke in relation to Matthew, much the same way Paul was relating to James — which is to say — he had made it his mission of correcting the earlier theological mistakes.

You may be wondering, how does Luke’s Gospel distinguish itself from Matthew’s gospel as a gospel for the Gentiles (as opposed to a gospel for the Jews). Let there be no doubt that Matthew and Luke share much in common, and Luke is very much indebted to the Gospel of Matthew as one of his main sources. After all, sixty four percent of Luke is made up of the same things found in Matthew. Nonetheless, it is in their differences where we can see their missions distinguish themselves.

For instance, I want us to look at a story from both Matthew and Luke, where a Gentile reaches out to Jesus for help. The Gentile in this case is a Roman Centurion who wants Jesus to heal his servant. Let us first look at how Matthew tells this story:

“As [Jesus] entered Capernaum, a centurion came forward to him, beseeching him and saying, ‘Lord my servant is lying paralyzed at my home, in terrible distress.’ And he said to him, ‘I will come and heal him.’ But the centurion answered him, “Lord I am not worthy to have you come under my roof; but only say the word, and my servant will be healed. For I am a man under authority, with soldiers under me; and I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes, and to another ‘Come,’ and he comes, and to my slave, ‘Do this,’ and he does it.’ When Jesus heard him, he marveled, and said to those who followed him, ‘Truly, I say to you, not even in Israel have I found such faith” (Matthew 8:5-10).

Now let us look at Luke’s version of the story,

“After [Jesus] had ended all his sayings in the hearing of the people he entered Capernaum. Now a centurion had a slave who was dear to him who was sick at the point of death. When he heard of Jesus, he sent to him elders of the Jews, asking him to come and heal his slave. And when they came to Jesus, they besought him earnestly, saying, ‘He is worthy to have you do this for him, for he loves our nation, and he built our synagogue.' And Jesus went with them. When he was not far from the house, the centurion sent friends to him, saying to him, ‘Lord do not trouble yourself, for I am not worthy to have you come under my roof; therefore I did not presume to come to you. But say the word and let my servant be healed. For I am a man set under authority, with soldiers under me: and I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes,; and to another “Come,” and he comes; and to my slave, ‘Do this,’ and he does it.’ When Jesus heard this he marveled at him, and turned and said to the multitude that followed him. ‘I tell you, not even in Israel have I found such faith’” (Luke 7:1-9).

In Matthew’s version, it is framed as a story about how Jesus was so well known that even people outside of Israel had faith in him — and not just any Gentiles either, the one’s with earthly power. However, taking this same story as his source, Luke does something slightly different with it. Instead of the Centurion coming directly to Jesus for help, he places the Jewish elders in the position of gatekeepers to Jesus, and it is they who tell Jesus that the Gentile is “worthy to have you do this for him, for he loves our nation, and built our synagogue.” The symbolism here is unmistakable. Through Luke’s Gospel, the Jewish elders have given their blessing to allow the Gentiles access to Jesus, because they also helped to build the church.

The most obvious pro-Gentile story in the Gospel of Luke, however, is the parable of the Good Samaritan. The people of Samaria and the people of Israel were known adversaries. Another way to put it, a Samaritan was the last person the Jewish community would think of as being “good.” This parable was obviously a challenge for Jews. As such, Jesus begins the parable by discussing the law. It is written, “And behold a lawyer stood up to put him to the test, saying, ‘Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?’ [Jesus] said to him, ‘What is written in law? How do you read?’ And he answered, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.’ And he said to him, ‘You have answered right; do this and you will live’” (Luke 10:25-28).

So as we can see, in Luke's Gospel the lawyer (i.e. a Jewish leader) asks Jesus what he should do for eternal life, and Jesus asks him how he understands the law. At which point the lawyer responds by reducing the entirety of the Law of Moses (which consists of 613 Laws) down to two: love God and love your neighbor. It should also be noted that in Matthew’s version of this story, it is Jesus who names the two most important laws. But like we saw with the story of the Centurion, Luke’s version puts the words in the mouths of the Jewish leaders — those attached to the Law.

What is more, as this story continues in Luke, the lawyer asks Jesus who he should consider his neighbor. It is at this moment that Jesus describes the Good Samaritan. He tells of how a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho was attacked by robbers and left for dead on the side of the road. Three different men came across this poor man in their travels. The first was a Jewish priest, who passed to the other side of the road when he saw him, the next was a Levite, who did as the priest before him had done, and he, too, crossed to the other side of the road. And third, was the Samaritan who saw the poor man and showed him compassion. He brought him to an inn and took care of him.

So as you can see in this parable — which is only found in the Gospel of Luke — it is the Gentile who is the example that we should emulate. This invoking of the Law, and then the reducing of it down to two commandments, and then using a Gentile as an example of God’s love reveals to us how and why we can see Luke’s Gospel as a clear response to Matthew’s. And thus, it can easily be seen as the “gospel for the uncircumcised” that Paul was talking about in his letter to the Galatians.

Let us recap where we are before we move forward: we have James, the first letter writer, who is very much connected with the theology and tradition found in the Gospel of Matthew — the first Gospel written. Next we have Paul, who is the second letter writer of the New Testament, and he is very much connected with the theology of the Gospel of Luke — the second Gospel written.

The Gospel of Mark: Peter's Theology

Lastly, we have Peter, who was arguably the third letter writer of the New Testament, and he is likewise connected with the Gospel of Mark — the third Gospel written.

Let us now explore this connection between Peter and Mark, and see how the Letters of Peter and the Gospel of Mark fit into the larger historical picture.

As we have already seen, Peter was put in the middle of James and Paul. After all, it was Peter who was accosted by Paul for siding with “the men sent from James” which as we saw is symbolic of Peter siding with Jewish tradition (i.e. faith and works) over a church that was accepting of both Jews and Gentiles alike, (i.e. preaching of faith without works).

Before we get to Peter’s connection with Mark and his Gospel, let us first look at the Letters of Peter to see if we can derive his theological understanding in order to see whether he was more like James or Paul in his preaching and belief.

Out of Peter’s two letters only the first one is of any real use to us at the present time. Not because the second one offers nothing of value, but rather because the authorship of the second letter of Peter has been doubted since as far back as the record goes.[29] And because we can not effectively argue in favor of Apostolic authorship of the Second Letter of Peter, I am simply going to ignore it in our present discussion. The first Letter of Peter, on the other hand, has certain marks of authenticity and thus offers us some useful information in regards to our mission at hand. The one passage in particular that I really want us to focus on in the First Letter of Peter reads as follows:

“And if you invoke as Father him who judges one impartially according to his deed, conduct yourselves with fear throughout the time of your exile. You know that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your fathers, not with perishable things such as silver or gold, but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish or spot. He was destined before the foundation of the world but was made manifest at the end of the times for your sake. Through him you have confidence in God, who raised him from the dead and gave him glory, so that your faith and hope are in God” (1 Peter 1:17-21).

In this passage, we see that Peter has once again positioned himself in the middle of James and Paul — at least theologically. The passage begins by saying that the Father judges one by their deeds, which sounds very much like the teaching of James about faith and works, but then it continues by saying that followers of Christ have been “ransomed from the futile ways inherited from [their] fathers,” which aligns more with the teachings of Paul in which Jesus has sacrificed himself for our sins, thus making works of the Law obsolete (i.e. “futile ways”).

In a similar fashion, the Gospel of Mark lies in the middle between Matthew and Luke. Biblical scholar B.H. Streeter appropriately described Mark’s relationship among the Synoptics as the “middle term.”[30] Oftentimes when you look at all three Gospels — side-by-side-by-side as they are telling you the same story — you will see that Matthew will have agreement with Mark’s passage, and Luke will have agreement with Mark’s passage, but Matthew and Luke will not be in agreement with each other against Mark. One can almost imagine Mark as the neutral ground between two feuding nations. (I will show you exactly how this happens in the next part of this essay.) Because of this shared space that is Mark’s Gospel, many scholars, including Streeter himself, believed that the Gospel of Mark came first. They contend that, on occasions of the triple tradition where all three Synoptics share the same story, the reason that Matthew and Luke are typically in agreement with Mark against each other is because they are each using Mark as one of their main sources. I disagree with this contention. I believe that the reason Mark is in agreement with Matthew and Luke is because he was using both of them as his sources, in an attempt to harmonize the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (how this happens will be explained at length).

I have highlighted how Peter and Mark occupy the middle ground between James and Paul, and Matthew and Luke, respectively. Nonetheless, the connection between Peter and Mark is profound, and much more than that seemingly simple reduction. In fact, there is a story in Acts that shows just how close the two actually were. We read that after an angel rescues Peter from prison, he turns to Mark in his time of need (Acts12:12).

And if turning to him in his time of need were not enough to highlight their close bond, Peter’s own words in his letter should settle the matter. For he refers to Mark as his “son.” Many of the early church fathers confirm this close bond they had.

As the Greek Apostolic Father Papias explains,

“Mark became Peter’s interpreter and wrote down accurately, but not in order, all he remembered of the things said and done by the Lord. For he had not heard the Lord or been one of his followers, but later, as I said, a follower of Peter. Peter used to teach as the occasion demanded, without giving thematic arrangement to the Lord’s sayings, so that Mark did not err in writing down some things just as he recalled them. For he had one overriding purpose: to omit nothing that he had heard and to make no false statements in his account.”[31]

The second century Bishop Irenaeus similarly said,

“Mark…the disciple and interpreter of Peter handed on to us in writing the things proclaimed by Peter.”[32]

And the church historian Eusebius elaborates on this:

“Peter’s hearers not satisfied with a single hearing or with the unwritten teaching of the divine message, pleaded with Mark, whose gospel we have, to leave a written summary of the teaching given them verbally, since he was a follower of Peter. Nor did they cease until they persuaded him and so caused the writing of what is called the Gospel according to Mark.”[33]

So as we can see, the connection between Peter and Mark is clear, and as strong (if not stronger) than the connection between James and Matthew or Paul and Luke. Furthermore, it is this historical framework — of connecting these three leaders of the early church with the their corresponding Synoptic Gospel — that I believe provides us with the most solid foundation on which to construct our solution to the Synoptic Problem.

Textual Evidence For Synoptic Solution

I want us now to go into the textual and form criticism that is at the heart of the Synoptic Problem. One could spend a lifetime studying all of the differences and similarities in side-by-side comparisons of the Synoptics, I am not going to do that here. What I am going to do is put forth a few solid arguments for each Gospel position for which I argue. That is, I will give reasons why Matthew is first, why Luke is second, and why Mark is third.

1. Why Matthew's Gospel is First

First let us begin with why I believe that the Gospel of Matthew was written first. As I have already shown, Matthean Priority is evidenced by history. Not only does it share a similar theology and audience as the Letter of James — the first letter written by the first leader of the church, but it was also believed to be the first Gospel by those closest to it (chronologically speaking). Papias, Ireneus, Origen, Eusebius, and Augustine all said that Matthew was first. I know these men are not always correct in their assumptions, but in this case I believe that they are. I want us to look at a passage that is shared by all three Synoptic Gospels, and we will see that in their differences the historical backstory of their formation comes into play.

Interestingly enough it is the story of “the calling of Matthew” that begins our side-by-side analysis. In Matthew’s Gospel the passage reads:

“As Jesus passed on from there, he saw a man called Matthew sitting at the tax office; and he said to him, ‘Follow me.’ And he rose and followed him” (Matthew 9:9).

In the Gospel of Luke, the same passage reads:

“After this he went out, and saw a tax collector, named Levi, sitting at the tax office; and he said to him, “Follow me.’ And he left everything and followed him” (Luke 5:27-28).

And in the Gospel of Mark, the passage reads:

“And as he passed on, he saw Levi, the son of Alphaeus sitting at the tax office, and he said to him, ‘Follow me.’ And he rose and followed him” (Mark 2:14).

The first thing that jumps out as a difference between these three is the switch from the name of Matthew to Levi (or Levi to Matthew if you subscribe to different synoptic hypothesis). Many people have simply conflated Levi with Matthew, saying it is just a different name for the same person. This does happen in scripture, such as Saul being also know as Paul. However, in every other case of name switching that I have studied, there is always some kind of explanation of the change — such as with Paul in the Books of Acts, “But Saul who is also called Paul” (Acts13:9), or with Mark, “John whose other name was Mark”(Acts 12:12) In the case of Matthew/Levi, however the change is never addressed or explained. So, where does this name change come from?

I want us to step back for a moment and think about all of the possibilities. I would invite anyone to make a case why one would change the name of Levi to Matthew; I can simply find no plausible reason for such a change. On the other hand changing the name form Matthew to Levi is actually a stroke of brilliance. The original Levi in scripture is one of Jacob’s sons, and thus one of the tribes of Israel. The Levites were the priests of Israel; Moses himself was a Levite; hence the reason why the religious rules set out by Moses in the Torah are compiled in the book of Leviticus. A Levite priest has many responsibilities, and one of them was to collect a ten percent tithe from the Israelites. This tradition goes back to the first priest named in scripture, man named Melchizedek who Abraham gave ten percent of his spoils of war as an act of sacrifice and gratitude to God. So in this light, it is a stroke of brilliance for Luke to change Matthew’s name to Levi. With this one simple change, Luke has shown great honor and respect to Matthew who wrote before him (and was obviously one of his sources). Luke has elevated him from being a simple tax collector, which was seen as one of the worst things one could be at the time, to a symbolic priest of God collecting on his behalf.

What is more, it is my contention Luke is writing his Gospel as a response to Matthew, and as such, he must feel that his Gospel is filling a void left by his predecessor. In other words, one could see Luke’s objective as: replacing Matthew; and in the passage above, he literally does just that. Luke simultaneously shows respect for what has come before him, elevating Matthew from tax collector to priest of God (i.e. a Levite), while at the same time removing Matthew from the passage entirely. As I said, Luke’s change from Matthew to Levi is a stroke of brilliance. The argument in favor of the change from Levi to Matthew, simply does not make sense in quite the same way. (Again, I invite anyone to attempt to prove me wrong on this account.)

What is more, there is another major clue in the above passages that Matthew wrote first, and it is Luke’s use of the words “tax-collector” in his passage. To understand why this phrase is so telling, we must turn to the naming of the twelve apostles (another passage shared by all three synoptics). In Matthew’s Gospel it is written:

“And [Jesus] called to him his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal every disease and every infirmity. The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the tax collector; James the Son of Alphaeus, and Thaddeus; Simon the Cananaean, and Judas Iscariot who betrayed him” (Matthew 10:1-4).

In Luke’s Gospel, the same passage reads:

“And when it was day, [Jesus] called his disciples, and chose from them twelve, whom he named apostles; Simon, whom he named Peter, and Andrew his brother, and James and John and Philip, Bartholomew, and Matthew, and Thomas, and James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon who was called the Zealot, and Judas the son of James, and Judas Iscariot, who became a traitor” (Luke 6:13-16).

And in Mark’s Gospel, the passage reads:

“And he appointed twelve, to be with him, and to be sent out to preach, and have authority to cast out demons: Simon whom he surnamed Peter; James the son of Zebedee and John the brother of James, whom he surnamed Boanerges, that is, sons of thunder; Andrew and Philip, and Bartholomew, and Matthew, and Thomas, and James the Son of Alphaeus, and Thaddeus, and Simon the Cananaean, and Judas Iscariot who betrayed him” (Mark 3:14-19).

Before I get into why these passages show why Luke’s use of the word “tax-collector” from the previous set of passages is important for our understanding that he wrote after Matthew, I want us first to notice that all three of the above passages name Matthew as one of the twelve disciples. Thus, if Levi and Matthew are the same person, why would Luke and Mark name Matthew here but not when he was sitting in the tax office? This seems to confirm our previous reasoning for the change from “Matthew” to “Levi” for Luke (and Mark). I want us now to notice that it is only in the Gospel of Matthew where Matthew is called a “tax collector” when the twelve apostles are named.

Now connecting it all together, it should not be difficult to understand that Luke who was writing after Matthew would have read this and known that Matthew was a tax collector, and then while rewriting the calling of Matthew at the tax office, removes his name and replace it with his profession. I previously argued that Luke changing Matthew’s name to Levi was to raise him up from tax collector to priest; nonetheless the argument could also be made the other way, in favor of trying to reduce Matthew to his Jewishness, which was very much in favor of the tradition of tithing and sacrifice. For Luke, who was writing for the Gentiles, and associated with Paul (who was very much opposed to works of the Law), could simply be challenging this whole idea of Jewish tradition. In Matthew’s Gospel, when the twelve apostles are named, Matthew is labeled a tax collector simply because that is what his job was and what he was known for; while in Luke’s Gospel, when Matthew/ Levi is called by Jesus, he is labeled a “tax-collector” in connection with the Jewish tradition (for better or worse).

These subtle changes do not make sense if Matthew was not written first. Let us think about it the other way for a moment, as if Luke (or Mark wrote first) and “Levi” was the name used first and he is described as a “tax collector,” but then when the twelve apostles are named neither “Levi” nor “tax-collector” is used by either Luke or Mark. That is, both Luke and Mark use “Levi” when the Apostle is called by Jesus and “Matthew” when the twelve apostles are named, which raises the question of why? There is no clear answer here; however, when Matthew is taken first, changing Matthew’s name to Levi and applying the “tax collector” label on him makes logical/historical sense.

There is also a huge inconsistency in Luke’s gospel in comparison with Matthew, which also suggests that he wrote later. Looking back to the calling of Matthew/Levi, Luke makes a big mistake in his wording: when Levi is called by the Lord, it is written, “he left everything and followed him.” As we continue reading, in the next passage of his Gospel, Levi is throwing a huge feast for Jesus at his house. The question must be asked: if Levi “left everything” to follow Jesus, then how does he still have his house and all of the ingredients to make a feast for Jesus? When we look at this same story in Matthew’s Gospel, however, Matthew does not “leave everything” to follow Jesus, and in the subsequent passage, the feast that is thrown for Jesus is with tax collectors, but nowhere does it say that it is at Matthew’s home. This inconsistency in Luke is an indicator that he was using Matthew (or Mark if you subscribe to another hypothesis) as a source, and it is what Goodacre refers to as “editorial fatigue.”[34] Editorial fatigue is when one evangelist is copying the story of another, but somewhere along the way he fails to adhere to the changes he has made throughout the entirety of the passage. To put it simply, the more consistent one’s story seems throughout, the more likely it was written first, which is to say original and not reliant on another's words for the material.

I could continue to go through passage after passage, comparing and contrasting all the little differences between the Synoptics in order to further prove my point that Matthew came first. But the truth is, that would turn this very long essay into a very long book, and at the current time that is not my goal. For now, let us acknowledge a few main points of my argument thus far:

— The church fathers all believed that Matthew was written first.

— The theology of Matthew’s Gospel aligns most closely with the first leader of the church James the Lord’s brother.

— The two references to “Matthew” in each of the Synoptics only make sense with Matthean priority.

2. Why Luke's Gospel is Second

It makes logical/historical sense that Luke, who was a missionary companion of the second Letter writer, Paul, would write a gospel in response to Matthew, in much the same way that Paul was responding to James. The Jews were converted first and then the Gentiles, thus the “gospel for the circumcised” (Matthew) was written first, and the “gospel for the uncircumcised” (Luke) was written second.

———

Most scholars can agree with the way in which I have ordered Matthew and Luke; however, most undoubtedly have an issue with me placing Mark third instead of first. There are multiple arguments in favor of Markan priority, not the least of which is the issue with explaining how Mark, which is the shortest Gospel, could write after Matthew and Luke and leave out so many important elements found in both Gospels of Jesus’s life — such as his birth, genealogy, and the Lord’s Prayer. I will address these major issues momentarily, for now I want us to step back, and recall the historical framework in which the Gospel of Mark was written.

This brings us back to Peter — who was put in the middle of James and Paul in Antioch — and Mark — who was Peter's interpreter, confidant, and “son,” whose Gospel likewise has been defined as the “middle term” between Matthew and Luke. Let us look at exactly how Mark is “the middle term” — existing between Matthew and Luke.

There is a story that is shared by all three Synoptics where Jesus healed the sick in the evening. Let us look at all three renditions. First let us look at Matthew, which says,

“That evening they brought to him many who were possessed with demons; and he cast out the spirits with a word, and healed all who were sick” (Matthew 8:16).

In Luke it is written:

“Now when the sun was setting, all those who had any that were sick with various diseases brought them to him; and he laid his hands on every one of them and healed them” (Luke 4:40).

Why Mark's Gospel is Third

Now look how Mark is made up of a combination of each of these two:

“That evening at sundown, they brought to him all who were sick or possessed with demons. And the whole city was gathered together about the door. And he healed many who were sick with various diseases, and cast out many demons” (Mark 1:32).

Mark is the convergence/ combination of Matthew and Luke, or the “middle term,” if you will. For instance, Matthew said “that evening” and Mark said “that evening” and Luke said when the “sun was setting” and Mark said “at sundown.” So where Matthew describes it one way, and Luke describes it another, Mark describes it BOTH ways, putting himself in agreement with BOTH. This happens yet again in the passage. Where Matthew says “possessed with demons” but Luke says “sick,” and sure enough Mark, as the middle term writes both phrases in the line, “sick or possessed with demons.”

Seeing how Mark is made up of what is present in both Matthew and Luke in such a way, it stands to reason that Mark can only be first of the Synoptics or last of the Synoptics.

Many scholars in favor of the former argue that Matthew and Luke are simply taking what they need from Mark, and cutting out the rest. That argument seems far less likely than Mark, as the last Synoptic writer trying to harmonize these two divergent Gospels (“a gospel for the circumcised” and “a gospel for the uncircumcised”). Think about it historically for a moment. You have this new church that is trying to unite two divergent ways of life, two opposing cultures, two different approaches to faith, and the contradictions in the two different teachings threaten to undermine the whole movement. As Abraham Lincoln famously said, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”[35] This is where Mark comes in. As we saw in the above passage, Mark brings together the two (at times) contradictory Gospels into a more unified theological whole.

The argument against this theory still remains: if Mark wrote after Matthew and Luke, why would he leave so much out of his Gospel that is found in the other two. What I find interesting about this “Mark-brevity” argument is that it fails to hold water on a passage by passage basis. That is, oftentimes when all three Gospels share the same story, it is Mark’s that is the longest of the three. All we need to do is look at the above passage for evidence of this. This makes sense after all; for if one were combining and harmonizing the work of two others then it seems likely that the passage would expand to fit the perspectives of both.

Scholar David Barrett Peabody also puts forth two more very convincing arguments in favor of Mark writing third. The first is sort of along the same lines as the previous argument, but it expands upon it generously. It is the “alternating agreement” argument. According to this contention, Mark alternates back and forth which Gospel he agrees with. That is, he will copy Matthew for two passages, and then Luke for two, then Matthew for three, then Luke for three. In fact, Peabody charts the alternating agreement out in great detail.[36]

Peabody’s most convincing argument for Mark being the last of the synoptics, however, is what is known in the field of Synoptic Problem study as “Markan Overlay” which describes the editorial idiosyncrasies that are completely unique to Mark. [37] One of the examples of Markan Overlay is his use of the word “again.” Mark uses the word fifteen times, and what is particularly interesting is that in all of the shared passages with Matthew and Luke, not once do they use the word in the Gospels.[38] This raises a major problem for those scholars who argue in favor of Markan Priority, because why would both Matthew and Luke, who are each supposedly using Mark as their source, leave out the word “again” in every single passage that has it. It makes a lot more sense to see the word as something that is unique to Mark because he is the one adding it to the work of the other two.

Let us return to the brevity of Mark in comparison to the other two for moment. Only three percent of Mark’s Gospel is completely unique to him. Scholars in favor of Markan Priority argue that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source — fifty six percent of Matthew and forty two percent of Luke is also found in Mark, and ninety-seven percent Mark is found in the other two. This raises the question of how did Matthew and Luke, each coming after Mark, combine to use essentially every last bit of Mark — practically leaving nothing unused. This view point requires many more sources and conjectures of origin. Think about it, if Mark is writing third, with a goal of combining and harmonizing Matthew and Luke, wouldn’t it make sense for him to do just that — and I mean that quite literally — he did JUST THAT. In other words, Mark’s goal was simply to harmonize the gospels of Matthew and Luke, and nothing else. It was not his place to add anything to them, so he didn’t.

The Synoptic Solution

Can the Great Literary Enigma Really Be Solved?

Ok, so we have explained the basis of the Synoptic Problem, we have looked at essentially every hypothesis that has existed throughout the centuries (both good and bad alike), and we have argued in favor of the Griesbach Hypothesis by establishing an historical foundation on which to build our argument. We followed that by doing a side-by-side comparison of some shared passages in order to use the textual evidence to confirm our theory. Nonetheless, after all of this, there is still the proverbial elephant in the room of my Synoptic Problem solution, and that is my disagreement with Markan Priority.